Six months have passed since my wife Jamie and I hiked through the Desolation Wilderness, a federally protected wilderness area in the Eldorado Forest, near South Lake Tahoe. The previous summer, we secured our permits for two days of through-hiking in Desolation during the first week of October, with an overnight, permitted stay slated for a site called Dick’s Pass. Located in the middle of a twenty-five mile stretch of the Pacific Crest Trail running from Echo Lake to Meeks Bay, at 9,400 feet Dick’s Pass is one of the higher peaks in the Eldorado Forest. Although regular hikers at lower altitudes throughout the Bay Area, my wife and I had not hiked or camped in the Tahoe area before. We also hadn’t done a multi-day through-hike anywhere in over ten years. Still, that summer we both had it in our heads to change that before the first Tahoe snows of 2018 fell. A quick internet search on my part came up with Desolation, and I don’t recall looking at anything past that. Truthfully, I picked the location solely for its intriguing name, and my wife agreed to it because she didn’t have any other suggestions. So, off to Desolation Wilderness we went.

Our plan was to reach Dick’s Pass a bit before sunset, so we’d have ample time find a good spot to pop the tent, and also get the lay of the land. We hooked up with the PCT at the south end of Echo Lake and from that starting point figured we’d have about twelve miles of mostly uphill hiking to do in the span of nine hours or so. It seemed doable. By the time we reached the sign shown above, we’d put in about an hour on a flat, leisurely stretch of trail that hugged the north shore of the lake most of the way. The sun was shining, it was about 55 degrees, and we had the place to ourselves. Easy. But we knew enough to know we had no idea what was coming.

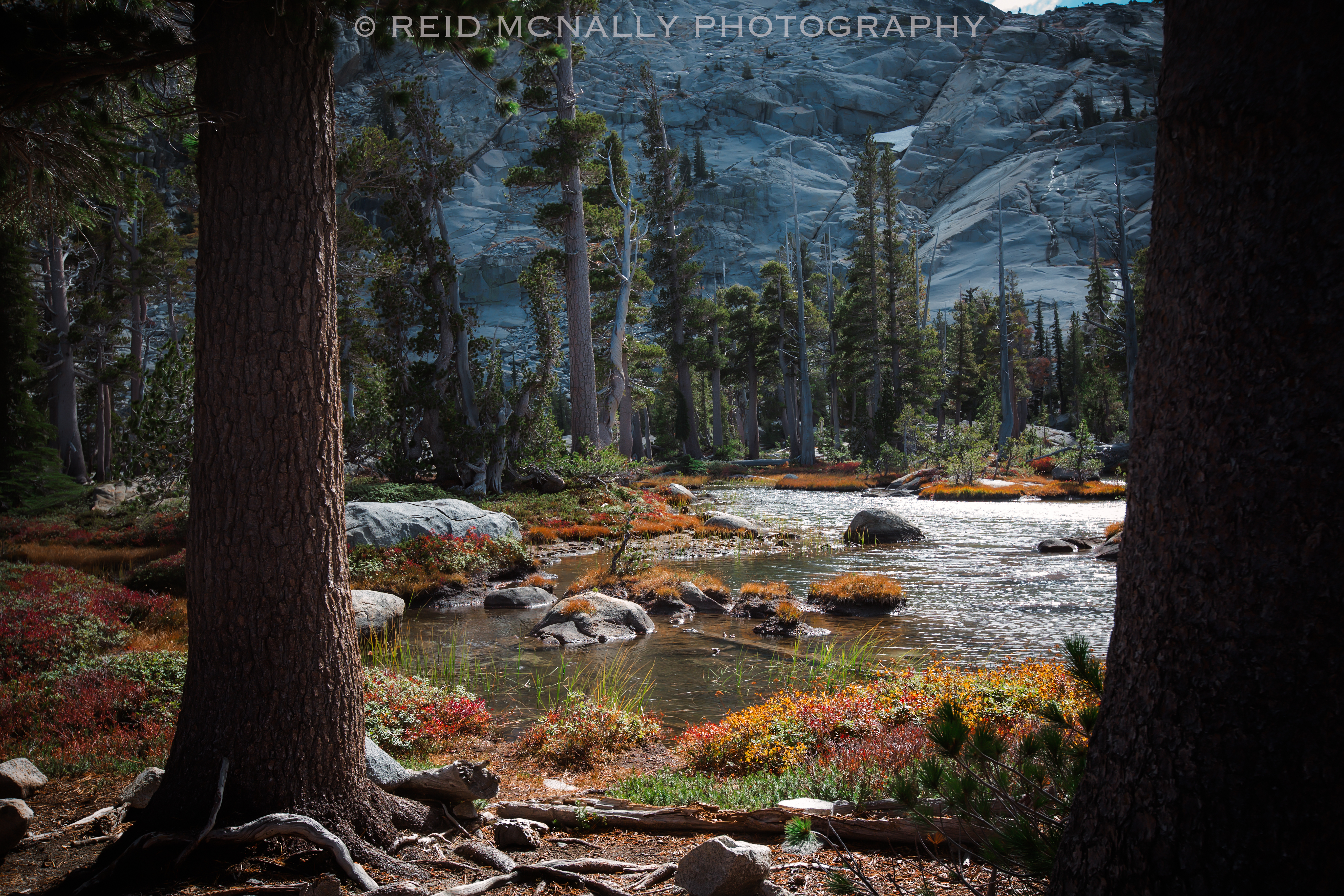

As soon as we passed the sign informing us we were officially entering the Desolation Wilderness, we began to climb. Echo Lake sits at about 7,400 feet and Dick’s Pass tops out at around 9,400. We knew we’d be heading uphill most of the way, but didn’t think too much about how much or where. About an hour past the sign, we found ourselves hiking through the flat, tranquil area above and it was the only setting like it during the two days. Spanning a half mile at best, our time within this peaceful place lasted only moments, yet its the stretch I’ll probably remember the most vividly.

The next five photos were taken around Lake Aloha, our first pit stop. I’m simply not a good enough photographer to do this transcendental location justice. Situated about five hiking miles from Echo Lake at an elevation of about 8,100 feet, it is almost indescribably beautiful. At the same time, it was here I began to appreciate why someone gave this area such an ominous name. There is a desolate aspect to the Aloha area, and as I would come to see, to other parts of Desolation as well. The word desolation is usually used to characterize something as ugly, bleak, or barren and I would not use those words to describe DW, yet well before we exited this stunning piece of the world, I came to find the name fitting, if not inspired.

As we knew from just our map, lakes and such were going to be a common sight, and soon after passing Lake Aloha we gave up trying to remember them all. It seemed there was a pond or lake around every other corner, all accessible fresh water sources we would regret not taking advantage of, farther down the road. The next few shots were taken over the couple hours following our break at Lake Aloha, which at this point was far behind us and well to our south.

It was an hour or so into the next morning before we’d appreciate the fortuitousness of our decision to pop the tent where we did, rather than push it to our permitted destination. Although we’d come across more than a few day-hikers before the official entry point, once past it we didn’t encounter another person for the rest of the day. Permits are required year-round within DW, but we were a week outside the official close of the season, so, in effect, no one was there to care where we camped. We were alone.

It was coming up on five o’clock and Jamie was feeling the day catch up with her. Putting in a few more uphill miles to reach Dick’s, over terrain which was a complete unknown, was just not advisable. We were now at about 8,700 feet, and I began to suspect Jamie was feeling the first enervating effects of higher altitude hiking. The next day would support these suspicions, as her fatigue became more pronounced with our climb to the summit. I am not suggesting altitude sickness as the cause, a serious condition which apparently can affect some people at elevations as low as 8,000 feet, but possibly just an understandable energy-drain, brought on by physically strenuous circumstances, coupled with lower oxygen accessibility.

Whatever the reason for her uncharacteristic exhaustion, because of it and the dropping sun we decided to pitch the tent where we stood. This turned out to be a lucky good call; as we’d discover the next day, we would have never made it to the summit by sundown, and instead would have been forced to overnight it ostensibly on the face of a craggy, wind-battered cliff.

We awoke hungry and excruciatingly sore. The night before had been bitterly cold and windy, with an interminably long-lasting hailstorm, all of which made for a fitful night’s sleep. In addition, I had probably stepped out to pee at least a dozen times, which aside from being an incredible nuisance, was something of which I should have taken note. Jamie had willed herself not to exit the tent once, yet had only caught snatches of restless sleep herself. So, if only to put all that unpleasantness behind us, we “awoke” shortly before the sun, packed up our gear, downed a few walnuts, took a few swigs from our dwindling water supply, and were back on the trail by 6 AM.

About an hour into the morning, things looked something like this.

Exactly seventeen minutes later, they looked like this, and continued to look like this for a good long time.

No more than a mile into the morning’s hike, both of us were experiencing problems: Jamie, energy-wise, was wiped out, and I was starting to feel the effects of serious dehydration, something this severe I’d only experienced once before, decades ago while crewing a boat at sea. We were at about 9,000 feet and nearing the ridge top when the photo above was taken. It was not until this point that I took into account the increased physical consequences that can be suffered at high altitude. It was a potentially costly mistake, which stemmed straight from our lack of experience with this riskier type of hiking. Jamie’s energy level and sluggishness did not improve until we began our descent of the ridge hours later, but it did stabilize at a point where she could mechanically move along at a slower but even pace. Meanwhile, my state only worsened, with every step becoming an intensifying exercise in muscle-cramping pain tolerance. And the whole time we had our brand-new water purifier neatly packed away! Better late than never, we put it to immediate use in a flowing stream we came upon just a few hundred vertical feet below the summit. It was entirely due to our inexperience and carelessness that over the last day-and-a-half we had passed by millions of gallons of clean, pure mountain water. But chalking it up to a valuable lesson learned the painful way, after a long drink of some of the best water in the world, we filled our canteens and resumed our trek to the top.

We made it to Dick’s Pass at 9:35 AM. As mentioned earlier, after passing the official DW entry point sign the day before, we came across nearly no one. The only other parties we did encounter, both shortly before reaching the summit, were a small group of athletic day-hikers and a fully loaded solo trekker. Coincidentally, all of them were French, which we picked up during an exchange of hellos.

After a short break at the top to take in the view and drop our packs for a bit, we were about to reload and begin our descent on the east side of the mountain, when a large company of trail runners — maybe two dozen of them in a tight, fast-moving formation — suddenly materialized. Heading for the west edge of the ridge from which we had just come, we flagged one down and asked her if she might know how far we had to go to reach Meeks Bay, a question we already knew the answer to but in our state of semi-delirium had all but forgotten. Glancing at her running watch, she said about six miles, and then took off like a shot to rejoin her group, which was now disappearing over the west horizon. Either in the commotion our question had been misconstrued, or her watch was wildly inaccurate, as we would discover/remember later, we were still over twice that distance from our final destination. Under the circumstances, however, although ignorance was nowhere near bliss, at the time it was a hell of a lot better than the truth. So, re-energized by the bit of encouraging, entirely false information, we initiated our descent.

Dropping over the east side of the ridge, what instantly caught our attention was the snow. As far as we could see and in every direction there were frosty dust piles, which made for a dreamlike setting. Below is one of more than a few shots I took while we made our way down this pleasant yet all too brief mile of so of the trail.

An hour or so later and about 2000 feet lower, we found ourselves making way through another surreal landscape, similar in feeling to Lake Aloha, yet also possessed of its own personality. With its unique, bulbous trees, perfectly placed boulders, and overall manicured appearance, the area was almost cartoonish, reminding me of the exaggerated mock-environmental assemblages one sees at theme parks. It was a beautiful little scene, but when exiting it both of us in unison remarked upon how strange it all was.

Just as the photo below was being taken, with a hiker heading up the trail we inquired again about the distance to Meeks. Also equipped with gadgetry meant to figure things like this out, he informed us we were about nine miles away. He also told us he’d begun his hike at Meeks, so we were resigned to accept his information invalidated that given to us by the woman at the summit a few hours before. This new distance also reconfirmed our own calculations, (now coming back to us) that we’d figured out the old fashioned way, modern gadgetry be damned. Regardless of this minor psychological setback, having returned to a more human-friendly altitude, Jamie was returning to her normal self. Unfortunately for me, my condition was not so quickly remedied. Since beginning our descent, I had been forced to set a shamefully slow hiking pace, which explained why we had covered a measly three to four miles of easy downhill hiking in nearly as many hours. Although we were still miles from nowhere and at about 7,000 feet, with increasing frequency people began popping up seemingly out of the ground, and accordingly every one of them flew past us with fresh legs powered by hydrated muscles. However, for the first time in over 27 hours, Jamie and I caught a hazy glimpse of Lake Tahoe in the distance, which again reinvigorated us, enough to inspire a lively conversation about all the food and drink we were going to squeeze into ourselves that night. Mostly, I talked about Gatorade.

By the time we passed the pristine scene below, one so close to perfect it seemed silly, we had passed by so many bodies of water it had almost become monotonous. Between Lake Aloha and this point, which is a distance of maybe fifteen miles on the trail, my guess is we had hiked by at least a dozen lakes, ponds, or streams. This section of Eldorado Forest is unquestionably a water-lover’s wet dream.

By the time we had reached the beginning of the end to our little adventure, Jamie could smell the finish line, somewhere unseen ahead. Fully recovered from her general state of debility, thanks to a friendly 6,500 foot elevation and a forgiving, relatively rock-free trail laid out before us, her spirits greatly improved, and mine as well, gnarled muscles aside. Day-hikers were now happily crawling about everywhere. I had a passing thought of sailors long at sea, who spot their first gull in the sky, and by its company know solid ground lies ahead.

When exiting a place like this, there could probably be no more fitting landscape to behold than one last pairing of lake and sierra, a final reminder to the visitor of nature’s implacability, uncompromising beauty, and timeless grandeur. A half-hour after this last photo was taken, we crossed a little metal foot bridge crossing a stream, and then suddenly we were walking through an asphalt parking lot and calling for an Uber on a smartphone with one bar of service available, looking to get a ride back to Echo Lake, forty minutes away by car. In two days, civilization hadn’t changed a bit, and even though what I was craving more than anything in the world at that moment was a big slice of pizza and a gallon of Gatorade, already I caught a part of me wanting to be back in that tent deep in the wilderness, in the middle of nowhere, wishing the hailstorm would stop.

Photos taken October 6 and 7, 2018.